|

even when the whites are fighting each other. |

|

even when the whites are fighting each other. |

![]() Well, it come to be that I was servin' with the King's African Rifles in 1917 when they was expandin' cuz the war wasn't going so good for the King. The Germans and the diseases had done drove most of the whites and British Indians from Africa.

Well, it come to be that I was servin' with the King's African Rifles in 1917 when they was expandin' cuz the war wasn't going so good for the King. The Germans and the diseases had done drove most of the whites and British Indians from Africa.

![]() The generals reckoned what more askaris (black African infantry) was a good idea, since the officers what paid attention knowed the blacks to be devils in a fight, and better against the bugs too. Well, when the King got ahold of me through no fault of my own, he sent me to train black Africans for the white man's war.

The generals reckoned what more askaris (black African infantry) was a good idea, since the officers what paid attention knowed the blacks to be devils in a fight, and better against the bugs too. Well, when the King got ahold of me through no fault of my own, he sent me to train black Africans for the white man's war.

![]() I was in British East Africa a couple of weeks waitin' for orders. I figured out real quick that dreamin' about light-skinned women was pointless, since there weren't none to be found. There was black women available and their rates was pretty cheap, too. The army couldn't get me orders to do nothin' useful, so I done some standin' around, and I done some walkin', and I done some more standin' around, cuz I was in the army. I also got to learnin' the talk of the blacks, Swahili.

I was in British East Africa a couple of weeks waitin' for orders. I figured out real quick that dreamin' about light-skinned women was pointless, since there weren't none to be found. There was black women available and their rates was pretty cheap, too. The army couldn't get me orders to do nothin' useful, so I done some standin' around, and I done some walkin', and I done some more standin' around, cuz I was in the army. I also got to learnin' the talk of the blacks, Swahili.

![]() I couldn't find nothin' else to do with my time, so I took to seein' a couple of the local whores there at the railhead in Voi pretty regular. Workin' on my Swahili, ya know. One time I noticed somethin' weird under the table of one of them when I dropped my watch. Prob'ly should'a just left the watch on to wash up. A small statue of some kinda funny black man, but his face was all blank and smooth. His head wasn't right and he had a big hole in his belly. Weird. I looked at it for a while, and finally asked her what it was. She jerked her head back, then kinda smiled and said, "Tommy, you don' wan' me start playin' wid dat ting. You wan' me start playin' wid dis ting." And she gimme seconds for free, so I left happy and didn't think nothin' of it. Next time I come back, tho, she was gone. Didn't matter much, cuz there was lots of 'em to choose from in Voi. After a while, I got sent to the 18th battalion, KAR. I had to walk a while cuz there was no trains in that direction, and I didn't see no wagons neither and wasn't nobody gonna gimme no mule.

I couldn't find nothin' else to do with my time, so I took to seein' a couple of the local whores there at the railhead in Voi pretty regular. Workin' on my Swahili, ya know. One time I noticed somethin' weird under the table of one of them when I dropped my watch. Prob'ly should'a just left the watch on to wash up. A small statue of some kinda funny black man, but his face was all blank and smooth. His head wasn't right and he had a big hole in his belly. Weird. I looked at it for a while, and finally asked her what it was. She jerked her head back, then kinda smiled and said, "Tommy, you don' wan' me start playin' wid dat ting. You wan' me start playin' wid dis ting." And she gimme seconds for free, so I left happy and didn't think nothin' of it. Next time I come back, tho, she was gone. Didn't matter much, cuz there was lots of 'em to choose from in Voi. After a while, I got sent to the 18th battalion, KAR. I had to walk a while cuz there was no trains in that direction, and I didn't see no wagons neither and wasn't nobody gonna gimme no mule.

![]() The sergeant seen me within minutes of me gettin' to camp, cuz the whites (and full blood Apaches like me) really stood out from the blacks. Sergeant Hogg been in the King's army since the Boer War, and he was redcoat down to his soul. He was tellin' me what (and how and when) to do to the Africans while walkin' me over to meet the leftenant. They gimme the corporal's stripes within ten minutes cuz I stood there and said "Yes, sir" and "No, sir" every time I was supposed to. The also gimme a .455 Webley, but it was an awkward, heavy, ugly damn thing. Too nose heavy to feel comfortable. Leftenant Higgins come from money. Turns out he was a pretty good officer, for an officer. Both the leftenant and the sergeant turned out to be calm men when the bullets was flyin' and I was happy to be servin' with them.

The sergeant seen me within minutes of me gettin' to camp, cuz the whites (and full blood Apaches like me) really stood out from the blacks. Sergeant Hogg been in the King's army since the Boer War, and he was redcoat down to his soul. He was tellin' me what (and how and when) to do to the Africans while walkin' me over to meet the leftenant. They gimme the corporal's stripes within ten minutes cuz I stood there and said "Yes, sir" and "No, sir" every time I was supposed to. The also gimme a .455 Webley, but it was an awkward, heavy, ugly damn thing. Too nose heavy to feel comfortable. Leftenant Higgins come from money. Turns out he was a pretty good officer, for an officer. Both the leftenant and the sergeant turned out to be calm men when the bullets was flyin' and I was happy to be servin' with them.

![]() One day pretty quick after I got there the sergeant sez to me, "Corporal Benton, there is a lot of disease in this country. Much of it lives in the black women hereabouts." I took the hint and quit dreamin' about black women, too, much less visitin' them. It was hard 'cuz there was whores on every corner callin' "I love you, Tommy" to me. From their point of view, the money pro'bly would'a been best with the white NCO's. The white officers wouldn't do 'em, and the black enlisted men had damn little money. I do look kindly on the King for the rum ration, tho. That was about the only thing for a white man in the King's army to do in Africa except wait and walk once the black women was off the menu. It was a hard war.

One day pretty quick after I got there the sergeant sez to me, "Corporal Benton, there is a lot of disease in this country. Much of it lives in the black women hereabouts." I took the hint and quit dreamin' about black women, too, much less visitin' them. It was hard 'cuz there was whores on every corner callin' "I love you, Tommy" to me. From their point of view, the money pro'bly would'a been best with the white NCO's. The white officers wouldn't do 'em, and the black enlisted men had damn little money. I do look kindly on the King for the rum ration, tho. That was about the only thing for a white man in the King's army to do in Africa except wait and walk once the black women was off the menu. It was a hard war.

![]() So my job was to teach the Africans to be soljurs. They was real good in the bush, but could get spooked too easy when they couldn't see what was goin' on. The sergeant and me had to take turns marchin' them around cuz they never got so tired that they couldn't keep on goin'. They was tough, and they liked to see what they was killin' up close. When the sergeant seen that I could shoot pretty damn good and wasn't scared of no bayonet, he left me alone to show hundreds of them blacks what they could do for fun with an Enfield.

So my job was to teach the Africans to be soljurs. They was real good in the bush, but could get spooked too easy when they couldn't see what was goin' on. The sergeant and me had to take turns marchin' them around cuz they never got so tired that they couldn't keep on goin'. They was tough, and they liked to see what they was killin' up close. When the sergeant seen that I could shoot pretty damn good and wasn't scared of no bayonet, he left me alone to show hundreds of them blacks what they could do for fun with an Enfield.

![]() When they was on the range, they was shootin' OK if they was shootin' one or two at a time, but when 50 or 100 rifles was goin' off in a hurry, damn but they would always get to shootin' high and higher and then even higher. When it was quiet in the shade and I was explainin' the sight picture to them, I figgured least half of 'em knowed what I was tryin' to tell 'em. On the range and later in the bush, they had hell hittin' things. I think it was cuz the sights got in the way of seein' what they was tryin' to kill. I never seen one of 'em what could beat me over any course of fire more'n two or three shots.

When they was on the range, they was shootin' OK if they was shootin' one or two at a time, but when 50 or 100 rifles was goin' off in a hurry, damn but they would always get to shootin' high and higher and then even higher. When it was quiet in the shade and I was explainin' the sight picture to them, I figgured least half of 'em knowed what I was tryin' to tell 'em. On the range and later in the bush, they had hell hittin' things. I think it was cuz the sights got in the way of seein' what they was tryin' to kill. I never seen one of 'em what could beat me over any course of fire more'n two or three shots.

![]() The second day on the range I was inspectin' a black's rifle when the bolt jammed. I made the soljur pry it open, field strip it, clean it, put it back together, carry it 3 miles to camp to get me a drink of water, then carry it and the 5 gallons of water back 3 miles to the range in under an hour. He done it, too. The rest of 'em learned the basics of cleanin' and shootin' a rifle real good after that, cuz carryin' water was real shameful for a warrior. I didn't have to use that one too often, cuz it worked so good.

The second day on the range I was inspectin' a black's rifle when the bolt jammed. I made the soljur pry it open, field strip it, clean it, put it back together, carry it 3 miles to camp to get me a drink of water, then carry it and the 5 gallons of water back 3 miles to the range in under an hour. He done it, too. The rest of 'em learned the basics of cleanin' and shootin' a rifle real good after that, cuz carryin' water was real shameful for a warrior. I didn't have to use that one too often, cuz it worked so good.

![]() Bayonets, tho, that was another thing entirely. Every single damn askari in Africa liked the bayonet better then the bullet. Even the Zulus with their spears what the sergeant told me about would rather stab ya than shoot ya any day. I dunno if he ever seen any real Zulus, but he talked like he knowed 'em real good. Most of my blacks could slice up any white man alive, blade to blade, 'specially after I was done with 'em. I was teachin' 'em the classic army method. Thrust on 1, smash the butt up and forward on 2, then slice down hard with the blade on 3. They had lots of fun but mostly in the bush they was blades first pokin' away. Steps 2 and 3 was usually forgot. Still, they liked it and fought like they was born to it. No fear. No exhaustion. No pain. When I was trainin' 'em, I always kept my Webley with me and loaded cuz I was really thinkin' what they was gonna give theirselves the battle lust and come tryin' to slice me. Didn't ever happen, tho.

Bayonets, tho, that was another thing entirely. Every single damn askari in Africa liked the bayonet better then the bullet. Even the Zulus with their spears what the sergeant told me about would rather stab ya than shoot ya any day. I dunno if he ever seen any real Zulus, but he talked like he knowed 'em real good. Most of my blacks could slice up any white man alive, blade to blade, 'specially after I was done with 'em. I was teachin' 'em the classic army method. Thrust on 1, smash the butt up and forward on 2, then slice down hard with the blade on 3. They had lots of fun but mostly in the bush they was blades first pokin' away. Steps 2 and 3 was usually forgot. Still, they liked it and fought like they was born to it. No fear. No exhaustion. No pain. When I was trainin' 'em, I always kept my Webley with me and loaded cuz I was really thinkin' what they was gonna give theirselves the battle lust and come tryin' to slice me. Didn't ever happen, tho.

![]() So, I trained Africans. After too little a while the generals figgured we was ready and sent us out to kill Germans. Now, the Germans was mostly Africans like the British was mostly Africans. We left camp with over 100 rifles in Company C and even more porters and cleanin' women and such. We rode trains and walked and waited and didn't see no Germans, black or white, for weeks. We done some guardin' of stuff what our Africans was more danger to than the German Africans. Then along come the war, and we was done takin' it easy.

So, I trained Africans. After too little a while the generals figgured we was ready and sent us out to kill Germans. Now, the Germans was mostly Africans like the British was mostly Africans. We left camp with over 100 rifles in Company C and even more porters and cleanin' women and such. We rode trains and walked and waited and didn't see no Germans, black or white, for weeks. We done some guardin' of stuff what our Africans was more danger to than the German Africans. Then along come the war, and we was done takin' it easy.

![]() The leftenant learned somethin' early on. He give a stripe to the toughest, smartest black in the company. The man's name was Mgumbono. When Leftenant Higgins was done marchin' us through the bush, he would ask Mgumbono what looked like the best place to sleep. The black warrior would gaze over the country and pick some spot that looked to all us whites like any other spot, but we had less disease in Company C than in any other company of the 18th battalion, KAR. He knowed somethin' about the bundu (African bush country), Mgumbono did.

The leftenant learned somethin' early on. He give a stripe to the toughest, smartest black in the company. The man's name was Mgumbono. When Leftenant Higgins was done marchin' us through the bush, he would ask Mgumbono what looked like the best place to sleep. The black warrior would gaze over the country and pick some spot that looked to all us whites like any other spot, but we had less disease in Company C than in any other company of the 18th battalion, KAR. He knowed somethin' about the bundu (African bush country), Mgumbono did.

![]() One day we was pushin' the Germans around East Africa, which was mostly lots of walkin'. We knowed they was out there 'cuz they would take a shot at us from time to time, but they was shootin' from real far off and mostly wanted us to just get tangled up from all the divin' and shoutin'. Our askaris didn't like it much, but after a while they was pretty much ignorin' the shots 'cuz wasn't nobody much gettin' hit.

One day we was pushin' the Germans around East Africa, which was mostly lots of walkin'. We knowed they was out there 'cuz they would take a shot at us from time to time, but they was shootin' from real far off and mostly wanted us to just get tangled up from all the divin' and shoutin'. Our askaris didn't like it much, but after a while they was pretty much ignorin' the shots 'cuz wasn't nobody much gettin' hit.

![]() We was marchin' thru the bush in different formations so the Germans wouldn't be able to set an ambush for us. Ya know, we would go in three columns for a while, then two skirmish lines, then one column with point and tail elements, changin' all the time. The leftenant figgured we was harder to count and predict that way, and I think the sergeant liked the idea after he got used to it. I thought it was real clever, myself. The King's army spent entirely too much effort being predictable.

We was marchin' thru the bush in different formations so the Germans wouldn't be able to set an ambush for us. Ya know, we would go in three columns for a while, then two skirmish lines, then one column with point and tail elements, changin' all the time. The leftenant figgured we was harder to count and predict that way, and I think the sergeant liked the idea after he got used to it. I thought it was real clever, myself. The King's army spent entirely too much effort being predictable.

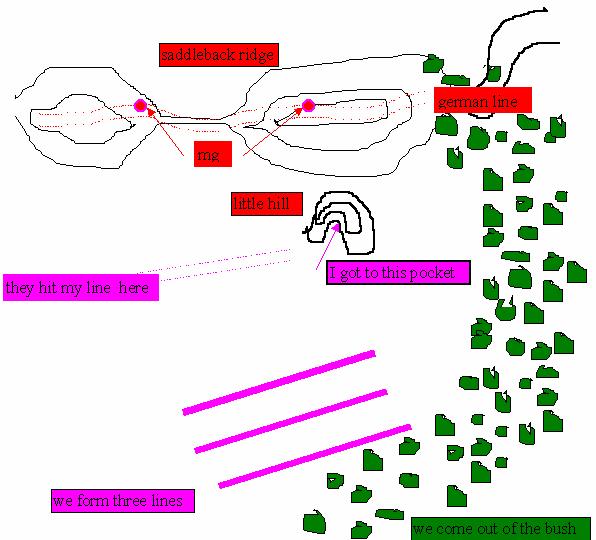

![]() We was supposed to occupy some little hills that day and meet up with somebody from the 14th KAR, but we knowed they was gonna be late 'cuz they missed our runners and we missed their runners and they wasn't where they was supposed to be. Well, our point element come out of the bush into a big clearing, hundreds of acres. They stopped and I went up with the sergeant to see what was to be seen. There was a saddleback ridge where we was supposed to meet the 14th. And a little hill below the ridge which made it harder to spread out when moving towards it. We didn't see nothin' but knowed the Germans was around 'cuz this was the only easy pass through the hills and they done been plinkin' at us all day. The sergeant pointed out to the leftenant that there was no need to hurry since there was no way the 14th could be there before mornin' and hurryin' across the open like that was what the Germans been waitin' for the us to do for weeks. The leftenant sez "Orders is orders" and forms us up in three skirmish lines, 100 yard apart. I got the first line on account of the leftenant bein' mad at me over a drunken bender concernin' the King's rum ration, but he was also with the first line. Like I said, he was a pretty good officer, for an officer. I was at the right end and he was near the left one. Mgumbono was with the second line, and Sergeant Hogg was with the third line.

We was supposed to occupy some little hills that day and meet up with somebody from the 14th KAR, but we knowed they was gonna be late 'cuz they missed our runners and we missed their runners and they wasn't where they was supposed to be. Well, our point element come out of the bush into a big clearing, hundreds of acres. They stopped and I went up with the sergeant to see what was to be seen. There was a saddleback ridge where we was supposed to meet the 14th. And a little hill below the ridge which made it harder to spread out when moving towards it. We didn't see nothin' but knowed the Germans was around 'cuz this was the only easy pass through the hills and they done been plinkin' at us all day. The sergeant pointed out to the leftenant that there was no need to hurry since there was no way the 14th could be there before mornin' and hurryin' across the open like that was what the Germans been waitin' for the us to do for weeks. The leftenant sez "Orders is orders" and forms us up in three skirmish lines, 100 yard apart. I got the first line on account of the leftenant bein' mad at me over a drunken bender concernin' the King's rum ration, but he was also with the first line. Like I said, he was a pretty good officer, for an officer. I was at the right end and he was near the left one. Mgumbono was with the second line, and Sergeant Hogg was with the third line.

![]() Sure enough the Germans had two mitrailleuse (machine guns) just behind the ridge and some rifles too. They opened up on us at about 300 yards. That was too early to work as well as it could have. I figured 18 to 24 rifles plus the two Maxims. Our line was spread too thin for the Maxims to get more than half a dozen before the askaris was on their bellies on the grass, and the rifles was pretty much out of range and couldn't have got more'n a couple more of us. The first shots hit a man just in front of me in the head and blowed it pretty much off. I wasn't close enough to see that it was his brains sprayin' around, but I just kinda knowed what that mist was made of. I was on my belly real quick, and I lost track of what was goin' on in the lines behind me. Since the Maxims was above us, they couldn't have done much to the lines behind while firin' at the first line. The fight was gonna turn into the Maxims butcherin' quick anybody what showed his head, and slowly killin' the KAR what was hidin' in the grass till it got dark. It was gonna be hours till dark. There was gonna be lots of dead KAR by then.

Sure enough the Germans had two mitrailleuse (machine guns) just behind the ridge and some rifles too. They opened up on us at about 300 yards. That was too early to work as well as it could have. I figured 18 to 24 rifles plus the two Maxims. Our line was spread too thin for the Maxims to get more than half a dozen before the askaris was on their bellies on the grass, and the rifles was pretty much out of range and couldn't have got more'n a couple more of us. The first shots hit a man just in front of me in the head and blowed it pretty much off. I wasn't close enough to see that it was his brains sprayin' around, but I just kinda knowed what that mist was made of. I was on my belly real quick, and I lost track of what was goin' on in the lines behind me. Since the Maxims was above us, they couldn't have done much to the lines behind while firin' at the first line. The fight was gonna turn into the Maxims butcherin' quick anybody what showed his head, and slowly killin' the KAR what was hidin' in the grass till it got dark. It was gonna be hours till dark. There was gonna be lots of dead KAR by then.

![]() There was lots of shoutin' and hollerin' in the grass. Most of the shoutin' was Swahili, but I heard enough to figgur that the leftenant was hit and we was all gonna be in trouble. Since I didn't like that idea at all, I reckoned I better do somethin' about it before things turned real bad. I crawled to the little hill real careful so wouldn't nobody see me. Since my askaris was hollerin' in Swahili and their askaris was understandin' Swahili just fine, I had to make sure none of mine shouted, "There goes the corporal to that little hill." Some of the KAR was shootin' up at the ridge without hittin' much, especially from the lines behind me, but it kept the Maxims busy with somebody other than me.

There was lots of shoutin' and hollerin' in the grass. Most of the shoutin' was Swahili, but I heard enough to figgur that the leftenant was hit and we was all gonna be in trouble. Since I didn't like that idea at all, I reckoned I better do somethin' about it before things turned real bad. I crawled to the little hill real careful so wouldn't nobody see me. Since my askaris was hollerin' in Swahili and their askaris was understandin' Swahili just fine, I had to make sure none of mine shouted, "There goes the corporal to that little hill." Some of the KAR was shootin' up at the ridge without hittin' much, especially from the lines behind me, but it kept the Maxims busy with somebody other than me.

![]() The Germans had made a mistake, I seen when I got to the little hill. They'd forgot it and left it uncovered, and it had a lee, completely blind to the Maxims and rifles on the ridge. It was also high enough what I could see the Germans who was busy shootin' down at the grass below me. I seen enough to figgur about 30 blacks and three whites. Anyway, the smoke from their Model 71 black powder Mauser rifles made the black Germans easy to spot. It prob'ly also meant that this was not the best Schutzetruppe in East Africa. I didn't get to thinkin' till later that three whites and two machine guns was a lot for only 30 blacks. We had three whites for 100 or so blacks. I never did figgur out what that meant. Shortly, I remembered about shootin' prairie dogs and then I worked me out a good plan.

The Germans had made a mistake, I seen when I got to the little hill. They'd forgot it and left it uncovered, and it had a lee, completely blind to the Maxims and rifles on the ridge. It was also high enough what I could see the Germans who was busy shootin' down at the grass below me. I seen enough to figgur about 30 blacks and three whites. Anyway, the smoke from their Model 71 black powder Mauser rifles made the black Germans easy to spot. It prob'ly also meant that this was not the best Schutzetruppe in East Africa. I didn't get to thinkin' till later that three whites and two machine guns was a lot for only 30 blacks. We had three whites for 100 or so blacks. I never did figgur out what that meant. Shortly, I remembered about shootin' prairie dogs and then I worked me out a good plan.

![]() When ya shoot prairie dogs, ya come up behind a ridge overlookin' their burrows. Without showin' anything ya don't have to, ya shoot the ones furthest away first. When ya can't see any more, ya nose up just a little and shoot them a little closer. Ya work yer way up shootin' closer and closer to the ridge till ya finally end up shootin' the ones at the bottom of the hill and closest to ya last. I remember once usin' a frozen cow turd to brace me for the long shots at them little critters one frosty mornin' back at the White Mountain res.

When ya shoot prairie dogs, ya come up behind a ridge overlookin' their burrows. Without showin' anything ya don't have to, ya shoot the ones furthest away first. When ya can't see any more, ya nose up just a little and shoot them a little closer. Ya work yer way up shootin' closer and closer to the ridge till ya finally end up shootin' the ones at the bottom of the hill and closest to ya last. I remember once usin' a frozen cow turd to brace me for the long shots at them little critters one frosty mornin' back at the White Mountain res.

![]() So, I come up the little hill behind the crest till I could just barely see one black German and when one of the Maxims fired a burst, I popped him. The Maxims done real good at makin' it hard to hear a single Enfield. Then I moved around to another spot on the little hill and nosed up again. I was real careful not to poke the barrel of my Enfield over the crest so nobody else could see it, and I was real careful not to shoot more'n once from any given spot nor to shoot when they wasn't shootin'. I took a while, but sooner or later I (and maybe somebody else from below) got all eight of 'em to the left of the left Maxim without the Germans catchin' on. I also got the three on the far right end of the line ,too. They pro'bly figured it was fire from below, cuz once in a while one of the KAR would pop off a shot.

So, I come up the little hill behind the crest till I could just barely see one black German and when one of the Maxims fired a burst, I popped him. The Maxims done real good at makin' it hard to hear a single Enfield. Then I moved around to another spot on the little hill and nosed up again. I was real careful not to poke the barrel of my Enfield over the crest so nobody else could see it, and I was real careful not to shoot more'n once from any given spot nor to shoot when they wasn't shootin'. I took a while, but sooner or later I (and maybe somebody else from below) got all eight of 'em to the left of the left Maxim without the Germans catchin' on. I also got the three on the far right end of the line ,too. They pro'bly figured it was fire from below, cuz once in a while one of the KAR would pop off a shot.

![]() I topped off the magazine on the Enfield, then nosed up. I fired three quick shots. The gunner, the white officer, and the loader. This time, I stayed up to cover the Maxim. The two whites still alive should have just left town while they was still ahead, but the one in charge sent two more blacks to crew the Maxim, and I got 'em both. Then they started thinkin' and caught on to me. I got behind the crest while the remainin' Maxim plowed dirt all over my little hill. I got the Enfield topped off, then nosed up to check on the gun I had got quiet. They was tryin' again to haul it back, and I got off a quick shot and got behind the hill again. The Germans had put one Maxim on each side of the saddleback, so I had a little spot where I could cover the one on the left without bein' seen by the one on the right. They had to abandon the gun on the left when they realized the spot I'd got myself into. I couldn't get the second Maxim and the remainin' rifles was also plowin' up the dirt on and around my little hill cuz they knowed where I was by then.

I topped off the magazine on the Enfield, then nosed up. I fired three quick shots. The gunner, the white officer, and the loader. This time, I stayed up to cover the Maxim. The two whites still alive should have just left town while they was still ahead, but the one in charge sent two more blacks to crew the Maxim, and I got 'em both. Then they started thinkin' and caught on to me. I got behind the crest while the remainin' Maxim plowed dirt all over my little hill. I got the Enfield topped off, then nosed up to check on the gun I had got quiet. They was tryin' again to haul it back, and I got off a quick shot and got behind the hill again. The Germans had put one Maxim on each side of the saddleback, so I had a little spot where I could cover the one on the left without bein' seen by the one on the right. They had to abandon the gun on the left when they realized the spot I'd got myself into. I couldn't get the second Maxim and the remainin' rifles was also plowin' up the dirt on and around my little hill cuz they knowed where I was by then.

![]() That's when Sergeant Hogg and Mgumbono got the remainin' British askaris formed up for a bayonet charge. When the officer with the Maxim seen them, he made another mistake (his last) and switched over to shoot at them. I figured his Swahili talkers couldn't shoot no better'n ours and was pro'bly tryin' to shoot the chargin' line of blacks anyhow, so I went ahead, popped up for five quick shots (and I do mean quick) to discourage the Germans from operatin' the other Maxim. I hit at least two of the three men at the second gun, so it got quiet and stayed quiet. I didn't stay up long enough to know for sure about the third one what was the loader.

That's when Sergeant Hogg and Mgumbono got the remainin' British askaris formed up for a bayonet charge. When the officer with the Maxim seen them, he made another mistake (his last) and switched over to shoot at them. I figured his Swahili talkers couldn't shoot no better'n ours and was pro'bly tryin' to shoot the chargin' line of blacks anyhow, so I went ahead, popped up for five quick shots (and I do mean quick) to discourage the Germans from operatin' the other Maxim. I hit at least two of the three men at the second gun, so it got quiet and stayed quiet. I didn't stay up long enough to know for sure about the third one what was the loader.

![]() Ya just can't believe the sound what the King's askaris make hollerin' out in a bayonet charge if ya ain't never heard if for yerself. Once the Maxims quit talkin', the German survivors took to their heels. I got positioned so I could cover both machine guns, and the bayonet charge swept up to the top. Mgumbono was the first man up and over the saddle, and I could see him tryin' hard to be the first to make sure every German in Africa was dead. After that, us whites took to callin' him "Bulletproof" amongst ourselves. When I finally walked up there later, I seen what he had got at least two what was too wounded to outrun him, and I didn't hear no shootin' neither. Later I heard the sergeant was real mad at him for chargin' down the other side, but one of the askaris what went close behind him said they killed another one back in the trees.

Ya just can't believe the sound what the King's askaris make hollerin' out in a bayonet charge if ya ain't never heard if for yerself. Once the Maxims quit talkin', the German survivors took to their heels. I got positioned so I could cover both machine guns, and the bayonet charge swept up to the top. Mgumbono was the first man up and over the saddle, and I could see him tryin' hard to be the first to make sure every German in Africa was dead. After that, us whites took to callin' him "Bulletproof" amongst ourselves. When I finally walked up there later, I seen what he had got at least two what was too wounded to outrun him, and I didn't hear no shootin' neither. Later I heard the sergeant was real mad at him for chargin' down the other side, but one of the askaris what went close behind him said they killed another one back in the trees.

![]() We had lots of dead and wounded. Most of our first line was out of action, and the second was pretty bad shot up, too. The leftenant was shot in both legs but was gonna live if the wounds didn't go septic. It was a hard war. He wrote some reports and dispatches on me and the hill and the saddleback and the Germans and the action. I wasn't much into readin' in those days, so I dunno what them reports said but turns out they gimme a medal for my trouble. A DSO to be exact. Prob'ly cuz the 18th KAR only captured three machine guns the whole war, and two of 'em was mine. Not a bad officer for an officer.

We had lots of dead and wounded. Most of our first line was out of action, and the second was pretty bad shot up, too. The leftenant was shot in both legs but was gonna live if the wounds didn't go septic. It was a hard war. He wrote some reports and dispatches on me and the hill and the saddleback and the Germans and the action. I wasn't much into readin' in those days, so I dunno what them reports said but turns out they gimme a medal for my trouble. A DSO to be exact. Prob'ly cuz the 18th KAR only captured three machine guns the whole war, and two of 'em was mine. Not a bad officer for an officer.

![]() Eventually, some of our support train showed up and took out the wounded. I never seen Leftenant Higgins again, but he wrote once from hospital to Sergeant Hogg so we knowed he was alive and goin' back to England in a wheelchair. The Sergeant decided to form a defensive perimeter on top of that ridge and hold for the reinforcements. All afternoon we had trouble keepin' the men in position 'cuz they kept sneakin' out in ones and twos to rob the dead (theirs and ours). We didn't have enough riflemen left to consider shootin' any of them looters. It was almost dark when the 14th showed. Sergeant Yarnock was in charge of Company D of the 14th KAR, cuz his leftenant got crazy sick and hadn't left the maps or orders where Yarnock could find them. So he said, anyhow.

Eventually, some of our support train showed up and took out the wounded. I never seen Leftenant Higgins again, but he wrote once from hospital to Sergeant Hogg so we knowed he was alive and goin' back to England in a wheelchair. The Sergeant decided to form a defensive perimeter on top of that ridge and hold for the reinforcements. All afternoon we had trouble keepin' the men in position 'cuz they kept sneakin' out in ones and twos to rob the dead (theirs and ours). We didn't have enough riflemen left to consider shootin' any of them looters. It was almost dark when the 14th showed. Sergeant Yarnock was in charge of Company D of the 14th KAR, cuz his leftenant got crazy sick and hadn't left the maps or orders where Yarnock could find them. So he said, anyhow.

![]() Now, the 14th KAR was harder to control than the 18th. None of their white NCO's could understand no Swahili at all. They had ones and twos and threes movin' in and out all night, lookin' for anything at all what the looters of the 18th had missed. Two shot up companies with no officers and damn few NCOs. As tired as I was, I couldn't sleep too good with them on sentry, 'cuz I knowed the damn sentries was sneakin' off. About three in the mornin' I was awake and lookin' around and seen the light of a decent sized fire a couple of miles off. I woke up Mgumbono who was sleepin' like a log and showed him the light. He didn't know what to make of it neither. We had no intention of goin' out to see what it was. Plenty of real mean things spend their whole lives stalkin' the African night.

Now, the 14th KAR was harder to control than the 18th. None of their white NCO's could understand no Swahili at all. They had ones and twos and threes movin' in and out all night, lookin' for anything at all what the looters of the 18th had missed. Two shot up companies with no officers and damn few NCOs. As tired as I was, I couldn't sleep too good with them on sentry, 'cuz I knowed the damn sentries was sneakin' off. About three in the mornin' I was awake and lookin' around and seen the light of a decent sized fire a couple of miles off. I woke up Mgumbono who was sleepin' like a log and showed him the light. He didn't know what to make of it neither. We had no intention of goin' out to see what it was. Plenty of real mean things spend their whole lives stalkin' the African night.

![]() It was a pretty bad place to be, that moonless night on top of the saddle. It was too dark to see nothin' or to control the troops, who were more dangerous than the Germans was gonna be till after dawn. Lightin' fires to see the troops was just gonna let the Germans see more about us than was necessary, and they wasn't gonna make no moves in that blackness neither. Besides, we was pro'bly gonna need all them stragglers I was so tempted to shoot for fightin' Germans when they did come in the mornin'. We couldn't afford to shoot none of them anyhow. Eventually I went back to sleep 'cuz there was nothin' else to do.

It was a pretty bad place to be, that moonless night on top of the saddle. It was too dark to see nothin' or to control the troops, who were more dangerous than the Germans was gonna be till after dawn. Lightin' fires to see the troops was just gonna let the Germans see more about us than was necessary, and they wasn't gonna make no moves in that blackness neither. Besides, we was pro'bly gonna need all them stragglers I was so tempted to shoot for fightin' Germans when they did come in the mornin'. We couldn't afford to shoot none of them anyhow. Eventually I went back to sleep 'cuz there was nothin' else to do.

![]() Come dawn and I was awake again, I reported it to Sergeants Hogg and Yarnock. The Germans runnin' from the fight would not have stopped so close nor lit so big a fire. A large German force was real possible. Yarnock sent a patrol out under some black corporal of his to scout. I could tell by what they was sayin' in Swahili that they was just gonna go out and have a smoke once they was out of sight. They was kinda mad about not gettin' no hot breakfast, but they was mostly just lazy buggers. They started out in not particularly the right direction and was soon not to be seen.

Come dawn and I was awake again, I reported it to Sergeants Hogg and Yarnock. The Germans runnin' from the fight would not have stopped so close nor lit so big a fire. A large German force was real possible. Yarnock sent a patrol out under some black corporal of his to scout. I could tell by what they was sayin' in Swahili that they was just gonna go out and have a smoke once they was out of sight. They was kinda mad about not gettin' no hot breakfast, but they was mostly just lazy buggers. They started out in not particularly the right direction and was soon not to be seen.

![]() Mgumbono got ours fed while I fumed about the 14th, but I got a decent plan together. Now, in the King's army, any man with more stripes was in charge regardless of his color. I saluted a black sergeant or two in my service for the King. However, if a black and a white had the same number of stripes, the white was always in charge. So, I had Mgumbono get our best squad out after breakfast. Their other choice would'a been buryin' dead men in the hot sun most of the day. My men had eaten and knew full well there was nothin' left worth stealin' on any of the dead, so they left in much better form than the first squad had.

Mgumbono got ours fed while I fumed about the 14th, but I got a decent plan together. Now, in the King's army, any man with more stripes was in charge regardless of his color. I saluted a black sergeant or two in my service for the King. However, if a black and a white had the same number of stripes, the white was always in charge. So, I had Mgumbono get our best squad out after breakfast. Their other choice would'a been buryin' dead men in the hot sun most of the day. My men had eaten and knew full well there was nothin' left worth stealin' on any of the dead, so they left in much better form than the first squad had.

![]() We stalked the first patrol into the bush when no sergeants were around to say nothin'. They left an easy trail to follow. Sure enough, they was havin' a smoke and a nap and a chat without even postin' no sentry. Me and Mgumbono was in there kickin' butts before they knowed what was happenin' to 'em. With half a dozen rifles from the 18th to back us, them buggers of the 14th was back on patrol with their corporal tryin' real hard to impress us so we didn't report him and maybe get him shot.

We stalked the first patrol into the bush when no sergeants were around to say nothin'. They left an easy trail to follow. Sure enough, they was havin' a smoke and a nap and a chat without even postin' no sentry. Me and Mgumbono was in there kickin' butts before they knowed what was happenin' to 'em. With half a dozen rifles from the 18th to back us, them buggers of the 14th was back on patrol with their corporal tryin' real hard to impress us so we didn't report him and maybe get him shot.

![]() Under closer supervision, them askaris of the 14th was much better soljurs than when they was left on their own. Their trail this time was harder to follow and they was a whole lot quieter. We worked around to where I'd seen the light and found a clearing without too much trouble. I couldn't believe what we seen there. It almost panicked the Africans. Even Mgumbono was shaken, but he kept steady.

Under closer supervision, them askaris of the 14th was much better soljurs than when they was left on their own. Their trail this time was harder to follow and they was a whole lot quieter. We worked around to where I'd seen the light and found a clearing without too much trouble. I couldn't believe what we seen there. It almost panicked the Africans. Even Mgumbono was shaken, but he kept steady.

![]() Most of a dead man was lyin' atop a rough pile of logs what kinda looked like an alter. He'd been skinned, but not very well, and there was enough bits of uniform and skin to see that he'd been a black German askari. There was plenty enough blood to show that he'd very likely been killed here. He'd been shot in his leg by a .30 calibre rifle, what would have slowed him down quite a bit, but pro'bly hadn't killed him. Chunks of him was thrown around the clearing. Some of them chunks had teeth marks what could'a been human, and some had teeth marks what for sure weren't human. We found four empty little piss-ant rimfire cartridges at one side of the pile of logs. Neither me nor Mgumbono had ever seed nothin' like them before. His belly was burned, too, from the inside. Some kinda real hot fire had flared in there and crisped his innards, but what was left of his limbs was still raw. It was a hard war.

Most of a dead man was lyin' atop a rough pile of logs what kinda looked like an alter. He'd been skinned, but not very well, and there was enough bits of uniform and skin to see that he'd been a black German askari. There was plenty enough blood to show that he'd very likely been killed here. He'd been shot in his leg by a .30 calibre rifle, what would have slowed him down quite a bit, but pro'bly hadn't killed him. Chunks of him was thrown around the clearing. Some of them chunks had teeth marks what could'a been human, and some had teeth marks what for sure weren't human. We found four empty little piss-ant rimfire cartridges at one side of the pile of logs. Neither me nor Mgumbono had ever seed nothin' like them before. His belly was burned, too, from the inside. Some kinda real hot fire had flared in there and crisped his innards, but what was left of his limbs was still raw. It was a hard war.

![]() We couldn't figgur out what exactly was goin' on. He'd prob'ly been shot in yesterday's battle and run for it but had been too slow to escape somebody. But who? Them stragglers and looters of the KAR? They'd had the time for it. My Africans weren't in the habit of skinnin' and eatin' Germans, and none of them from the 14th would admit to it neither. I knowed they had their own gods, but I never seen nothin' that brutal. There was a few natives out there in the bundu with some harsh customs, but we never found none in that neck of the woods what was at all known for that kinda thing. There was plenty of real mean critters stalkin' the African night. I was a little afraid of a mutiny when I ordered them to bury the man, but there was enough discipline to hold them together and they got it done, scared though they was. Even them buggers of the 14th made decent soljurs if not left to their own laziness.

We couldn't figgur out what exactly was goin' on. He'd prob'ly been shot in yesterday's battle and run for it but had been too slow to escape somebody. But who? Them stragglers and looters of the KAR? They'd had the time for it. My Africans weren't in the habit of skinnin' and eatin' Germans, and none of them from the 14th would admit to it neither. I knowed they had their own gods, but I never seen nothin' that brutal. There was a few natives out there in the bundu with some harsh customs, but we never found none in that neck of the woods what was at all known for that kinda thing. There was plenty of real mean critters stalkin' the African night. I was a little afraid of a mutiny when I ordered them to bury the man, but there was enough discipline to hold them together and they got it done, scared though they was. Even them buggers of the 14th made decent soljurs if not left to their own laziness.

![]() We went back to the saddle ridge and reported the dead body, ignorin' the problems of the 14th's patrol. We got orders finally to pull back to a relatively nearby village, and was happy to get the bad influence of the 14th away from our men before our men also took to shirkin' at every chance. We garrisoned the town and looked for anything what could explain that night's butchery but couldn't find nothin'.

We went back to the saddle ridge and reported the dead body, ignorin' the problems of the 14th's patrol. We got orders finally to pull back to a relatively nearby village, and was happy to get the bad influence of the 14th away from our men before our men also took to shirkin' at every chance. We garrisoned the town and looked for anything what could explain that night's butchery but couldn't find nothin'.

![]() After that, me 'n the 18th Battalion, KAR, done a lot more walkin', pushin' the Germans around. We was in and out of the bush and in and out of officers for a couple of months. We seen some more action, but nothin' as bad as the saddleback. When we finally chased the Germans out of German East Africa, we thought the war was over in Africa. The damn Germans had other plans, tho. They just kept stayin' ahead of us on into Portuguese East Africa. Better'n the trenches in France, anyhow. Africa was mostly walkin' and tryin' not to catch nothin'.

After that, me 'n the 18th Battalion, KAR, done a lot more walkin', pushin' the Germans around. We was in and out of the bush and in and out of officers for a couple of months. We seen some more action, but nothin' as bad as the saddleback. When we finally chased the Germans out of German East Africa, we thought the war was over in Africa. The damn Germans had other plans, tho. They just kept stayin' ahead of us on into Portuguese East Africa. Better'n the trenches in France, anyhow. Africa was mostly walkin' and tryin' not to catch nothin'.

![]() By that point, pretty much all of the King's whites and Indians was out of the African war. There was just a few officers and NCOs like me out in the bush. The local Africans wasn't so tired of it as I was, but they was still pretty tired of it. Both the Germans and the Portuguese was real hard on the black natives. Anyhow weren't none of them natives down there cared a lick for the well-bein' of a soljur of another tribe, be he white or an askari from three villages over.

By that point, pretty much all of the King's whites and Indians was out of the African war. There was just a few officers and NCOs like me out in the bush. The local Africans wasn't so tired of it as I was, but they was still pretty tired of it. Both the Germans and the Portuguese was real hard on the black natives. Anyhow weren't none of them natives down there cared a lick for the well-bein' of a soljur of another tribe, be he white or an askari from three villages over.

![]() I was managin' to stay in the fight even tho the fever and sickness was botherin' me, just not bad enough to go into hospital, where we figgured yer chances of dyin' was higher than in the bush. The war in Portuguese East Africa was pretty much like the war in German East Africa. Walkin'. Shootin'. Lots of dyin'. Some killin'. More walkin'.

I was managin' to stay in the fight even tho the fever and sickness was botherin' me, just not bad enough to go into hospital, where we figgured yer chances of dyin' was higher than in the bush. The war in Portuguese East Africa was pretty much like the war in German East Africa. Walkin'. Shootin'. Lots of dyin'. Some killin'. More walkin'.

![]() One day, me and "Bulletproof" Mgumbono was escortin' a supply train some miles back of where the officers reckoned the fightin' was. We had a couple dozen askaris from the 18th, somethin' like fifty porters, and some mules which wasn't quite dyin' of nothin' in particular. We was carryin' enough for us to keep on walkin', dyin', and killin' a little longer.

One day, me and "Bulletproof" Mgumbono was escortin' a supply train some miles back of where the officers reckoned the fightin' was. We had a couple dozen askaris from the 18th, somethin' like fifty porters, and some mules which wasn't quite dyin' of nothin' in particular. We was carryin' enough for us to keep on walkin', dyin', and killin' a little longer.

![]() We was mostly workin' at keepin' the mules walkin' in the right direction and wasn't spendin' enough time nor trouble lookin' for Germans, but they was workin' hard at lookin' for us. I was cursin' them damn mules cuz every one was gettin' stuck in the same mud hole and had to be drug out the other side when shots rang out and our askaris went to ground. Them porters dropped their loads and was lots more interested in gettin' back to the rear than they had been in gettin' to the front.

We was mostly workin' at keepin' the mules walkin' in the right direction and wasn't spendin' enough time nor trouble lookin' for Germans, but they was workin' hard at lookin' for us. I was cursin' them damn mules cuz every one was gettin' stuck in the same mud hole and had to be drug out the other side when shots rang out and our askaris went to ground. Them porters dropped their loads and was lots more interested in gettin' back to the rear than they had been in gettin' to the front.

![]() I think the Germans was hopin' we would light out too, cuz they wanted our supplies more'n anything else. Although they never seemed to lack for guns or bullets, the Germans (black and white) we seen before that day had been real skinny, and this batch turned out to be every bit as hungry.

I think the Germans was hopin' we would light out too, cuz they wanted our supplies more'n anything else. Although they never seemed to lack for guns or bullets, the Germans (black and white) we seen before that day had been real skinny, and this batch turned out to be every bit as hungry.

![]() Well, the 18th KAR was not the troop they wanted to meet, and that was not the day they wanted to meet 'em, and without knowin' how many we was up against, Mgumbono took ten askaris to the left, while I supplied coverin' fire with the remainin' troop, half of what was wounded or worse. I stayed in the mud hole for about five minutes of shootin' while Mgumbono and his troops went into the trees and around. I got one decent shot the whole time. I doubt my askaris hit anything but trees, and them just barely. Them damn mules was real unhappy to be millin' around, but the ones what had been dragged out of the mud could not get back through it without help. After another ten minutes, one of the askaris comes back and sez they got the Germans on the run. I had my troops cut the supplies loose from five of the mules what hadn't been hit by anything, then we rode them damn things past where the fightin' had moved to. We got past the Germans usin' them stupid mules, then jumped off on the high ground and shot up the Germans as they tried to get by us. When they seen they was whipped, one white corporal and the last two blacks surrendered. Mgumbono and some askaris come up to them from one side, me and some more from the other.

Well, the 18th KAR was not the troop they wanted to meet, and that was not the day they wanted to meet 'em, and without knowin' how many we was up against, Mgumbono took ten askaris to the left, while I supplied coverin' fire with the remainin' troop, half of what was wounded or worse. I stayed in the mud hole for about five minutes of shootin' while Mgumbono and his troops went into the trees and around. I got one decent shot the whole time. I doubt my askaris hit anything but trees, and them just barely. Them damn mules was real unhappy to be millin' around, but the ones what had been dragged out of the mud could not get back through it without help. After another ten minutes, one of the askaris comes back and sez they got the Germans on the run. I had my troops cut the supplies loose from five of the mules what hadn't been hit by anything, then we rode them damn things past where the fightin' had moved to. We got past the Germans usin' them stupid mules, then jumped off on the high ground and shot up the Germans as they tried to get by us. When they seen they was whipped, one white corporal and the last two blacks surrendered. Mgumbono and some askaris come up to them from one side, me and some more from the other.

![]() It was common to take whatever prisoners might have what was of any value, and of course we searched them for money, food, papers, cigarettes, weapons. These Germans was pretty lean, all told. I figgured lookin' at them that they was mostly hopin' for a meal out of our supplies when they started the shootin'. Mgumbono had already helped himself to the NCO's binoculars when he found a funny lookin' pistol in the guy's pocket. The German really didn't want to give it up, and Mgumbono had to work to pull it away from him. Me and Mgumbono was lookin' at it for a while. It had a short barrel which poked out between two of yer fingers, and ya squeezed it to make it go off. Some kinda revolver lookin' thing. Don't know if he'd been thinkin' about usin' it on us or not.

It was common to take whatever prisoners might have what was of any value, and of course we searched them for money, food, papers, cigarettes, weapons. These Germans was pretty lean, all told. I figgured lookin' at them that they was mostly hopin' for a meal out of our supplies when they started the shootin'. Mgumbono had already helped himself to the NCO's binoculars when he found a funny lookin' pistol in the guy's pocket. The German really didn't want to give it up, and Mgumbono had to work to pull it away from him. Me and Mgumbono was lookin' at it for a while. It had a short barrel which poked out between two of yer fingers, and ya squeezed it to make it go off. Some kinda revolver lookin' thing. Don't know if he'd been thinkin' about usin' it on us or not.

![]() The German NCO started talkin' a blue streak when he should'a been lookin' humble, but it wasn't English or Swahili or Apache or Mexican so I don't know what he said. After a couple minutes of the German's hollerin', Mgumbono sez kinda quiet in Swahili "I wonder if it works" and shoots the NCO in the back of the head with it. BOOM. Mgumbono looked almost as surprised as any of the rest of us there, but he real quick gets over it and shoots the two blacks in the chest with it. POP. POP. POP. POP. Click. Well, the Germans was more surprised than me, I suppose. I couldn't believe it. A soljur like me and I just stared until it was over. It was a hard war. And ya know, when Mgumbono reloaded the little thing, then it hit us both. The empties was the same little piss-ant cartridges we seed back at the log alter after the fight at the saddleback. At the time it was just a real curious thing, but now the thought of it gives me the shakes.

The German NCO started talkin' a blue streak when he should'a been lookin' humble, but it wasn't English or Swahili or Apache or Mexican so I don't know what he said. After a couple minutes of the German's hollerin', Mgumbono sez kinda quiet in Swahili "I wonder if it works" and shoots the NCO in the back of the head with it. BOOM. Mgumbono looked almost as surprised as any of the rest of us there, but he real quick gets over it and shoots the two blacks in the chest with it. POP. POP. POP. POP. Click. Well, the Germans was more surprised than me, I suppose. I couldn't believe it. A soljur like me and I just stared until it was over. It was a hard war. And ya know, when Mgumbono reloaded the little thing, then it hit us both. The empties was the same little piss-ant cartridges we seed back at the log alter after the fight at the saddleback. At the time it was just a real curious thing, but now the thought of it gives me the shakes.

![]() And if I was upset then, things got worse and I forgot all about cartridges. One of my askaris found a little black statue on one of the other half dozen dead black Germans. It had a no face and a big hole in its belly. If it was not the one that I'd seen under the whore's table in Voi, I couldn't tell them apart without seein' both of them at the same time. And I realized for the first time that the dead man from after the saddleback fight looked real similar. And when I seen that damn statue, I just sat there starin' at it long after Mgumbono had taken it away. Cuz, ya see, it was burnin' and squirmin' while I watched it, even tho I knowed that nobody else could see it do that. At least that's the way I remember it. And that was way beyond curious and way beyond the shakes. It was prob'ly the next day before I remembered that I was in the army. Maybe it was just the fever gettin' to me again.

And if I was upset then, things got worse and I forgot all about cartridges. One of my askaris found a little black statue on one of the other half dozen dead black Germans. It had a no face and a big hole in its belly. If it was not the one that I'd seen under the whore's table in Voi, I couldn't tell them apart without seein' both of them at the same time. And I realized for the first time that the dead man from after the saddleback fight looked real similar. And when I seen that damn statue, I just sat there starin' at it long after Mgumbono had taken it away. Cuz, ya see, it was burnin' and squirmin' while I watched it, even tho I knowed that nobody else could see it do that. At least that's the way I remember it. And that was way beyond curious and way beyond the shakes. It was prob'ly the next day before I remembered that I was in the army. Maybe it was just the fever gettin' to me again.

![]() We, of course, reported that there had been no prisoners taken, and Mgumbono took the pistol with the rest of the NCO's ammunition with him to carry in his pocket and get shot for having it in his own good time. We gathered up our askaris, our mules, and our porters and went on with the war.

We, of course, reported that there had been no prisoners taken, and Mgumbono took the pistol with the rest of the NCO's ammunition with him to carry in his pocket and get shot for having it in his own good time. We gathered up our askaris, our mules, and our porters and went on with the war.

![]() Not long after that the fever took me real bad, and I had me a vision after I went into hospital. The white doctor called it a halloosinashun, but us Apaches know a vision when we see one.

Not long after that the fever took me real bad, and I had me a vision after I went into hospital. The white doctor called it a halloosinashun, but us Apaches know a vision when we see one.

![]() There was a white man with a crazy look in his eyes that only white men get when the gods speak to them. This one was dressed all in white and was walkin' through the grass. It started out quiet, then he started to touch himself in various places, and noises came out. The noises were chaos. There was a kinda rhythm like gunfire. Unpredictable but continuous. He touched his elbow and his arm and his knee and his chest and the noises changed up and down when he did. The sound was havoc. It was loud but not loud like battle. Louder than man's music. More like the music of a god. There was a melody of sorts, but I never knew what was comin' next before it came. I think that maybe an elbow or a knee always sounded about the same when he hit it, but his hands moved too fast to tell for sure. He walked and made these sounds but did not say anything. I do not know whether he was the vigor of life or the evil of a demon. Good or evil I could not tell.

There was a white man with a crazy look in his eyes that only white men get when the gods speak to them. This one was dressed all in white and was walkin' through the grass. It started out quiet, then he started to touch himself in various places, and noises came out. The noises were chaos. There was a kinda rhythm like gunfire. Unpredictable but continuous. He touched his elbow and his arm and his knee and his chest and the noises changed up and down when he did. The sound was havoc. It was loud but not loud like battle. Louder than man's music. More like the music of a god. There was a melody of sorts, but I never knew what was comin' next before it came. I think that maybe an elbow or a knee always sounded about the same when he hit it, but his hands moved too fast to tell for sure. He walked and made these sounds but did not say anything. I do not know whether he was the vigor of life or the evil of a demon. Good or evil I could not tell.

![]() After time passed in the Indian way, another, taller, man appeared. He wore black in the manner of the white gunslingers of my father's day. His skin was brown. I could not tell if he was Indian or a white man who had spent his life in the sun and rain. He had black hair under a flat brimmed hat and said nothin'. His face was hard to see clearly. He did not look crazy like the other one, tho. He had gunslinger's eyes, movin' constantly in the dim under his hat. He had on a long coat and pulled out a horn like the white man's cavalry used in my grandfather's day. He blew a note, pure and strong on the horn. The note did not change. It was not louder than the chaos of the crazy man, but you could hear it in its simplicity. He would stop and breathe, then blow again. Sometimes the note would be different, but he did not change it after he started to blow it. I do not know whether the man in black was the purity of life or the simplicity of death. Evil or good I could not tell.

After time passed in the Indian way, another, taller, man appeared. He wore black in the manner of the white gunslingers of my father's day. His skin was brown. I could not tell if he was Indian or a white man who had spent his life in the sun and rain. He had black hair under a flat brimmed hat and said nothin'. His face was hard to see clearly. He did not look crazy like the other one, tho. He had gunslinger's eyes, movin' constantly in the dim under his hat. He had on a long coat and pulled out a horn like the white man's cavalry used in my grandfather's day. He blew a note, pure and strong on the horn. The note did not change. It was not louder than the chaos of the crazy man, but you could hear it in its simplicity. He would stop and breathe, then blow again. Sometimes the note would be different, but he did not change it after he started to blow it. I do not know whether the man in black was the purity of life or the simplicity of death. Evil or good I could not tell.

![]() Although I did not think he could, the crazy white man started to beat himself faster and faster. The chaos got wilder. Louder he could not go, but faster and faster he could. And did. The man in black and the man in white battled. It was a war. Neither tired, neither yielded. Time passed in the Indian way. Simple and complex battled. Life and death fought. The man in black took his horn and put it back in his coat. He climbed up all by hisself onto a pile of logs. He raised his hands above his head as though he had won. The chaos of the white man continued, a little slower, a little quieter. The black man reached into his coat pocket, and pulled out somethin' which I knew had to be a weapon. Without seein' it clearly cuz of the darkness that seemed to follow it around, I was sure I had seen it before. He shot once at the white man, who did not seem to notice. He then shot himself till it was empty, but I could not count in the vision and do not know how many times it fired. Many. The black man then put the weapon back in his pocket and then sorta burned up from the inside of all the little bullet holes. He had a look of victory before his face disappeared and he shriveled in the heat. And when the smoke cleared, there was just ashes. The white man walked and picked up a small black statue from the ashes and put it in his pocket. And the statue was still movin' by itself. And again, I knew without seein' it clearly that I had seen it twice before. The apparently victorious white figure walked slowly out of sight, still making noise. The vision faded to leave me sweatin' in the African night.

Although I did not think he could, the crazy white man started to beat himself faster and faster. The chaos got wilder. Louder he could not go, but faster and faster he could. And did. The man in black and the man in white battled. It was a war. Neither tired, neither yielded. Time passed in the Indian way. Simple and complex battled. Life and death fought. The man in black took his horn and put it back in his coat. He climbed up all by hisself onto a pile of logs. He raised his hands above his head as though he had won. The chaos of the white man continued, a little slower, a little quieter. The black man reached into his coat pocket, and pulled out somethin' which I knew had to be a weapon. Without seein' it clearly cuz of the darkness that seemed to follow it around, I was sure I had seen it before. He shot once at the white man, who did not seem to notice. He then shot himself till it was empty, but I could not count in the vision and do not know how many times it fired. Many. The black man then put the weapon back in his pocket and then sorta burned up from the inside of all the little bullet holes. He had a look of victory before his face disappeared and he shriveled in the heat. And when the smoke cleared, there was just ashes. The white man walked and picked up a small black statue from the ashes and put it in his pocket. And the statue was still movin' by itself. And again, I knew without seein' it clearly that I had seen it twice before. The apparently victorious white figure walked slowly out of sight, still making noise. The vision faded to leave me sweatin' in the African night.

![]() This is the problem with visions. Ya don't know who fights for yer soul and who fights to destroy it. I did not know if the defeat of the man in black was good or bad for me or my people or the King's African Rifles. It takes a medicine man of many moons to have the knowin' of these things. I do know that "Bulletproof's" shootin' of the white German NCO was not a good thing, but a man should not keep such things as a pistol like that unless he is prepared to accept the results of havin' 'em.

This is the problem with visions. Ya don't know who fights for yer soul and who fights to destroy it. I did not know if the defeat of the man in black was good or bad for me or my people or the King's African Rifles. It takes a medicine man of many moons to have the knowin' of these things. I do know that "Bulletproof's" shootin' of the white German NCO was not a good thing, but a man should not keep such things as a pistol like that unless he is prepared to accept the results of havin' 'em.

![]() Cuz of the general confusion amongst the King's doctors, for an unusual long time I could do anythin' I wanted as long as I was in my bed at 0530 and at 2200. And after thinkin' on the vision for a couple weeks of gettin' over the fever, I figgured I'd might outta find me a black medicine man and ask him what he thought it meant. As long as I could get back by 2200, the army didn't much care.

Cuz of the general confusion amongst the King's doctors, for an unusual long time I could do anythin' I wanted as long as I was in my bed at 0530 and at 2200. And after thinkin' on the vision for a couple weeks of gettin' over the fever, I figgured I'd might outta find me a black medicine man and ask him what he thought it meant. As long as I could get back by 2200, the army didn't much care.

![]() I asked the askaris in hospital with me about finding me a local "medicine man." Didn't translate well. "Witch doctor" translated better, tho I wasn't sure I was gonna get what I was lookin' for. "One who sees inside his eyes" finally got me what I wanted. They ended up sendin' me to a small village a couple hours away from the base to a little tiny fella what looked like he was about a hundred years old. It took a while to get down to business jabberin' Swahili and gettin' him to trust me, but eventually I got to tellin' him about my vision. In tryin' to explain what bothered me, I got to tellin' him about Mgumbono and the little pistol and the movin' statue. He was burnin' somethin' thick and sweet while I talked. And then I got to tellin' him about the burnt man after the battle and the little piss-ant cartridges and the whore and her statue, although hers wasn't movin'.

I asked the askaris in hospital with me about finding me a local "medicine man." Didn't translate well. "Witch doctor" translated better, tho I wasn't sure I was gonna get what I was lookin' for. "One who sees inside his eyes" finally got me what I wanted. They ended up sendin' me to a small village a couple hours away from the base to a little tiny fella what looked like he was about a hundred years old. It took a while to get down to business jabberin' Swahili and gettin' him to trust me, but eventually I got to tellin' him about my vision. In tryin' to explain what bothered me, I got to tellin' him about Mgumbono and the little pistol and the movin' statue. He was burnin' somethin' thick and sweet while I talked. And then I got to tellin' him about the burnt man after the battle and the little piss-ant cartridges and the whore and her statue, although hers wasn't movin'.

![]() When I was done, he done some mumblin' and some smokin' and some thinkin' and then got to lookin' real sad and kinda afraid. "Officer Benton," he said to me in his crackly voice, and I didn't correct him. "This vision is of a great evil. An ancient god of a people much older than mine. It is a curse to say his true name. We who know of him call him the Faceless One. Perhaps this demon was imprisoned by another demon ages ago. Now perhaps one of his faithful has set in motion a plan to release him. Or perhaps it is just a game of the gods. A little of the old one's essence lives there in the weapon, in the spaces between the spaces the white men know. And it hungers. The pistol finds the one who owns it the easiest way to ease that hunger. The white man's war offers it much, although not even the white man's war can fill it."

When I was done, he done some mumblin' and some smokin' and some thinkin' and then got to lookin' real sad and kinda afraid. "Officer Benton," he said to me in his crackly voice, and I didn't correct him. "This vision is of a great evil. An ancient god of a people much older than mine. It is a curse to say his true name. We who know of him call him the Faceless One. Perhaps this demon was imprisoned by another demon ages ago. Now perhaps one of his faithful has set in motion a plan to release him. Or perhaps it is just a game of the gods. A little of the old one's essence lives there in the weapon, in the spaces between the spaces the white men know. And it hungers. The pistol finds the one who owns it the easiest way to ease that hunger. The white man's war offers it much, although not even the white man's war can fill it."

![]() He sat down and smoked my free cigarettes a while, sayin' nothin'. "Yes. The weapon seeks to sacrifice its owner to another, who will then carry it to his own doom. My people have an ancient saying. 'The faithful make the best sacrifice.' The weapon seeks life force to fill the spaces between the spaces. And when those spaces are satisfied, the Faceless One will again walk this world. The statue is the doorway through which he will come. The weapon is the key to open that doorway. If this cycle of sacrifice is not stopped, He will pass through. Or maybe we would go to him. Either would be very, very bad. For your people. For my people. Even the whites. Some things are worse than death." Now, the medicine man didn't actually know nothin' about doorways nor keys while livin' in no grass hut, of course. But, the way he did describe it using animal sexual organs just don't translate well and so I just kinda told ya' what he meant.

He sat down and smoked my free cigarettes a while, sayin' nothin'. "Yes. The weapon seeks to sacrifice its owner to another, who will then carry it to his own doom. My people have an ancient saying. 'The faithful make the best sacrifice.' The weapon seeks life force to fill the spaces between the spaces. And when those spaces are satisfied, the Faceless One will again walk this world. The statue is the doorway through which he will come. The weapon is the key to open that doorway. If this cycle of sacrifice is not stopped, He will pass through. Or maybe we would go to him. Either would be very, very bad. For your people. For my people. Even the whites. Some things are worse than death." Now, the medicine man didn't actually know nothin' about doorways nor keys while livin' in no grass hut, of course. But, the way he did describe it using animal sexual organs just don't translate well and so I just kinda told ya' what he meant.

![]() He sat there some more, maybe dozin' off, maybe just thinkin'. He didn't say nothin' that made no sense at all after that. After some more pleasant smokin' and a typical unpleasant East African supper of boiled everything, I went back to hospital in time to keep the doctors happy. I was pretty unhappy, tho. The medicine man was prob'ly right that the pistol was not good for the health of anyone near it, and my friend "Bulletproof" Mgumbono was carryin' it. Not a good sign for him. I knowed him to be a true friend and the best man with a bayonet I'd ever seen, maybe the best in Africa, and now it looked like I'd be tryin' to get him to gimme somethin' he might not wanna give up.

He sat there some more, maybe dozin' off, maybe just thinkin'. He didn't say nothin' that made no sense at all after that. After some more pleasant smokin' and a typical unpleasant East African supper of boiled everything, I went back to hospital in time to keep the doctors happy. I was pretty unhappy, tho. The medicine man was prob'ly right that the pistol was not good for the health of anyone near it, and my friend "Bulletproof" Mgumbono was carryin' it. Not a good sign for him. I knowed him to be a true friend and the best man with a bayonet I'd ever seen, maybe the best in Africa, and now it looked like I'd be tryin' to get him to gimme somethin' he might not wanna give up.

![]() A week or so later the 18th KAR was pulled back to a base nearby to rest and regroup. I was sure that it was a sign, since goin' AWOL was deadly serious in them days in Africa and now I didn't have to take that risk. I went to the camp right after roll call, and found Company C. They'd been reinforced by Companies D and E, and there was just barely as many riflemen as when we'd left Voi for the war not that long ago. God, that was hell to realize. It was a hard war. Since officers was almost nonexistent, the NCO's was workin' real hard to get things organized. I found Mgumbono explainin' shovels to some recruits. We was damn glad to see each other again. I didn't have no chance to talk to him about the medicine man or the vision till after supper cuz of all the recruits runnin' around havin' to be told what to do all the time.

A week or so later the 18th KAR was pulled back to a base nearby to rest and regroup. I was sure that it was a sign, since goin' AWOL was deadly serious in them days in Africa and now I didn't have to take that risk. I went to the camp right after roll call, and found Company C. They'd been reinforced by Companies D and E, and there was just barely as many riflemen as when we'd left Voi for the war not that long ago. God, that was hell to realize. It was a hard war. Since officers was almost nonexistent, the NCO's was workin' real hard to get things organized. I found Mgumbono explainin' shovels to some recruits. We was damn glad to see each other again. I didn't have no chance to talk to him about the medicine man or the vision till after supper cuz of all the recruits runnin' around havin' to be told what to do all the time.

![]() He stayed calm and happy when I talked about the vision, but when I told him what the medicine man had thought of it, I could see in his eyes that he weren't gonna give up the cursed pistol without a fight. And I knowed I couldn't take him in no fist fight or knife fight. I could kill him in a gunfight more likely than not, but didn't want no part of that. Unless it had to come to that. I let the talk go on to solderin' like it usually does, catchin' up on what they been up to since I left them. I went back to hospital and got myself discharged the next mornin' and returned to my unit later that afternoon after a serious bender in town. I convinced myself over a bottle of really bad scotch whiskey that I had to steal the damn pistol from a natural warrior without gettin' caught or killed doin' it. And the statue. And destroy 'em both. I managed to get to camp successfully, have some supper, and fall asleep real early. All without bein' seen by no officers at that.